David with his A-frame model.

By David Gregorie

|

|

David with his A-frame model. |

My father was always interested in flying and was constructing successful flying model aircraft in his early teens. As a boy, he was desperately keen to get into the air himself.

The picture on the right shows him, aged 14 or 15, at Havelock North with a model aircraft he had made. He made a similar model for me in the 1940s. It flew, but not very convincingly. It was probably underpowered.

These models were known as A-frames, from the shape of the structure supporting the wings and propellers. They had a canard layout with the elevators at the front and the wing at the rear — like a Concorde. The rear-mounted, rubber-powered propellers rotated in opposite directions, giving it great stability. Martin tells me that this design was an example of the first successful type of flying model, dominating competition flying in the UK into the early 1920s.

Dad left Nelson College when he had completed his fifth form year at the end of 1915 and came home to Gorge End to help Grandad on the farm. Uncle Eric, in his turn, left the College at the end of his fifth form year in 1917 and came home to Gorge End.

Earlier in 1917, Dad had volunteered for the Royal Flying Corps and went to Sockburn, near Christchurch, to enrol at the Canterbury Flying School.

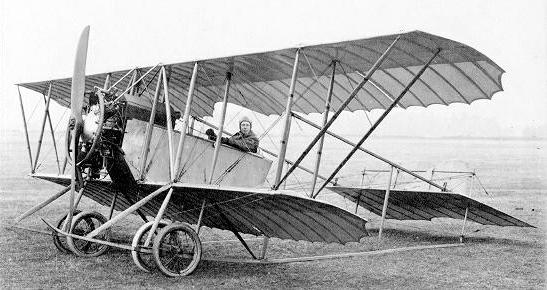

He was among the first hundred pupils of the school (see The First Hundred Pilots) and trained in a variety of Caudron biplanes, which were primitive in the extreme as can be seen from the accompanying photograph.

|

|

A Caudron dual control basic trainer. (See also 1st Caudron in NZ, Caudron biplanes). Most two seat biplanes were flown from the rear seat if they were being flown solo. Picture supplied by the RNZAF Museum, Christchurch, New Zealand. |

Two other Pahiatua names appear in the list from the CFS: Ernest Miller (23) and Ron Sinclair (38). Ernest and Halah Miller were life-long friends of Mum and Dad and I've known their four children all my life. Ron Sinclair was a friend of Dad's, but not a close one.

I have known Ivan Rawnsley's (29) daughter Gillian for many years. It was she who gave me the list of graduates from the CFS together with a photo of her father in a Caudron aeroplane.

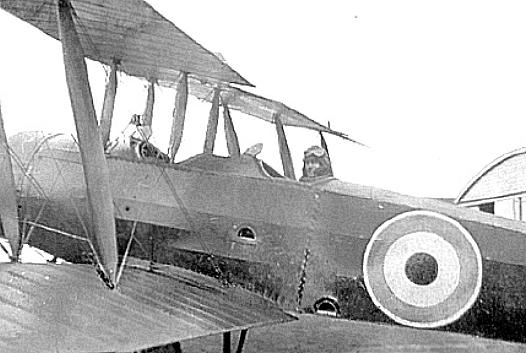

Dad earned his Canterbury Flying School wings on February 6, 1918, as the 36th graduate of the School and was immediately posted to England. He joined the RFC training group at Oxford and completed his training in the Avro 504K, a much more up-to-date aeroplane than the antiquated Caudron. Aircraft technology, driven by the war, was advancing rapidly.

Later that year he received his RAF wings and his commission as a lieutenant in the newly-formed Royal Air Force. He also held a British Civil Pilot's licence issued by the Royal Aero Club, which was the only aviation licence-granting authority in the UK at the time.

|

|

|

Dad with a single seat Caudron. |

Lt. David Gregorie, RAF. |

|

|

Dad sitting in an Avro 504K. |

After the war Dad returned to work at Gorge End with Grandad and Uncle Eric. He kept up his interest in flying and joined the New Zealand Squadron of the RAF Reserve, going to Sockburn once a year to maintain his flying hours and for advanced training

My nephew John Hennebry has Dad’s wings and flying licence. He also has a part of the propeller from he Avro 504K pictured below, which over-ran the runway at Sockburn sometime in the early 1920s, when Dad was still flying in the RAF Reserve. Dad was somewhat cagey about who actually committed this indiscretion, but maintained that it wasn't him.

|

|

|

The crashed Avro 504K. |

A second view of the crashed Avro 504K at Sockburn, Christchurch. My father is crossing the scene right foreground. Note that he is wearing RAF uniform except for his hat! |

Dad was grounded sometime in the early '20s for successfully doing a loop in a 504K at Sockburn. The 504K model used in New Zealand was underpowered and not stressed for aerobatics, therefore it couldn't do a loop, therefore Dad had better not set foot in Sockburn ever again, or so Dad told us.

But the real reason why Dad gave up flying was more down to earth. He had started the Forest Nursery in Pahiatua in the mid-1920s and he had fallen in love with Lilian James. They wanted to get married. He had neither the time nor the money for flying.

But flying had not been not driven from his mind. Whenever a plane flew over our home in the 1930s, which wasn’t very often, we went outside to see it and Dad tried to explain to me how it worked. I found it hard to understand, aged 5 or 6, why an aeroplane didn’t need wheels on its roof to run along the sky.

In 1962, when I was teaching in Mount Maunganui, I took Dad up for a flight in a Piper Tripacer, his first flight for exactly forty years. He commented that it felt and sounded much the same as in the 1920s but was much less draughty.